Catcalls and plaudits for Peter Jackson’s 3D HFR (High-Frame-Rate for the technically challenged) version of The Hobbit remind film makers everywhere that people, not machines, create the magic of movies.

3D HFR may well be “the next greatest thing” in the film business. Or maybe it’s not. But knowing matters less than you might suppose. Over 120 years of movie history, countless “next greatest things” have trampled in as elephants and fluttered off as midges. Do you remember Synchroscope, a sound-on-disc recording system? Remember a similar product, the Cinematophone? Maybe a gizmo collector does. But millions of movie lovers remember a well imagined movie because, once it bubbles up from nowhere, the imagination of talented filmmakers continues to flow forever. However rapidly or slowly a 3D HFR image changes, your movie is your vision.

Consider this half dozen former “next greatest things of the movies!”:

1. Smell-O-Vision (Synesthesia Movie)

1. Smell-O-Vision (Synesthesia Movie)

In 1960, Mike Todd Jr. released The Scent of Mystery in Smell-O-Vision. The movie promised everything. Widescreen Todd-AO. 8-track Todd-Belock wrap- around stereo sound system. Jack Cardiff, cameraman on The Red Shoes and three other Michael Powell movies, directed. Denholm Elliot, Peter Lorre (M), and Paul Lukas (The Lady Vanishes) headlined a stellar cast. Hans Laube, who invented the Smell-O-Vision system, earns credits as “osmologist,” the only such credit in the history of movies. A souvenir booklet containing a LP record of the sound track listed smells viewers would inhale during the movie. Delivering the “next greatest thing” in this case were tubes that wafted scents—peach, tobacco, perfume, wood shavings, shoe polish, roses, baked bread, coffee, lavender, peppermint and horses— to every seat in the theater. In the Cinestage Theater in Chicago, Smell-O-Vision tubes twisted for a mile. While The Scent of Mystery played twice a day at the Ritz in Los Angeles, Behind the Great Wall, a competing scented movie, dropped scents on viewers from air-conditioner ducts a block away down Wilshire Boulevard. “I didn’t understand the picture. I had a cold,” comedian Henny Youngman allegedly quipped about Smell-O-Vision.

2. Percepto! (Multi-Media Perceptual Field)

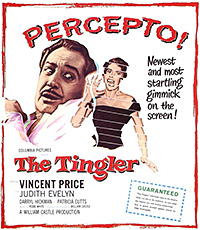

William Castle in 1959 concocted this comically macabre next greatest thing to enhance The Tingler, a horror film. In the film, a parasitic centipede – “The Tingler” – tingles at the base of spinal column of those who feel paralyzing fear. Inside its host, the tingler eventually grows lethal, except when the host disgorges fear in screams of terror. In a on-screen introduction, Castle forewarns audience members smitten with the actors’ terror to scream “any time you are conscious of a tingling sensation.” When actors on screen (and paid shills in the audience) eventually do uncork screams of terror, audience members in selected unmarked seats (in major market theaters) experienced inexplicable tingles. The projectionist had depressed a button. Buzzers secreted beneath their seats vibrated suddenly.

William Castle in 1959 concocted this comically macabre next greatest thing to enhance The Tingler, a horror film. In the film, a parasitic centipede – “The Tingler” – tingles at the base of spinal column of those who feel paralyzing fear. Inside its host, the tingler eventually grows lethal, except when the host disgorges fear in screams of terror. In a on-screen introduction, Castle forewarns audience members smitten with the actors’ terror to scream “any time you are conscious of a tingling sensation.” When actors on screen (and paid shills in the audience) eventually do uncork screams of terror, audience members in selected unmarked seats (in major market theaters) experienced inexplicable tingles. The projectionist had depressed a button. Buzzers secreted beneath their seats vibrated suddenly.

Audiences laughed off Percepto! as a gimmick.

3. Edwina Booth. (Pre-marketed Actress)

Left to right: Edwina Booth, Duncan Renaldo, Harry Carey, Mutia Omoolu. “Trader Horn” publicity shot.

If MGM publicists had succeeded, movies’ next greatest thing circa 1932 was to have been one Edwina Booth. Never heard of Edwina Booth? MGM anointed her to star in Trader Horn (1931) and packed her off to East Africa to cavort in a skimpy bra and a wispy loincloth as the long lost “white goddess” of an African tribe. While Willard Van Dyke’s film crew played cards, drank gin, and waited for sound recording equipment to arrive on location, tsetse flies gorged on Edwina Booth. She contracted “jungle fever” – malaria, “allegedly due to her harrowing experiences in exposing her almost nude body to the horrors of the African jungle.” While Booth passed the 1930s as an enfeebled recluse, newspapers strung out purple paragraphs reporting her as blind, moribund, sequestered in a “sunless room behind black painted windows,” intending to take up psychiatry, “neither dead nor alive, merely breathing, a beautiful shell in which a stubborn heart refuses to quit,” “the delicate nerve ends of her blonde skin burned by the glare of the African sun,” transformed to brunette by African sun that altered her body chemistry, and above all consumed with suing MGM for $1,000,000 and restitution of her promise, her beauty and her youth.

Instead of Edwina Booth, the MGM peroxide blonde bombshell of the 1930s turned out to be Jean Harlow, who, at twenty-six, perished of kidney failure.

4. Warner Bros. Grandeur. (1930s widescreen format)

70 mm “Grandeur” frame, The Big Trail (1930)

70 mm “Grandeur” frame, The Big Trail (1930)

Two decades before Merian C. Cooper opened This Is Cinerama in 1952, Warner Bros. had already released and withdrawn a movie shot in both conventional 35 mm and shot in a 2:10:1 70 mm format. The movie was The Big Trail. Dubbed “Grandeur” by Warner Bros. marketers, widescreen was to be movie’s next greatest thing of the 1930s. In Arthur Edeson’s 70 mm viewfinder, widescreen endowed the Raoul Walsh western with a sweep as wide as the west itself. But Grandeur never really happened. Release prints buckled in projectors. Exhibitors resisted investing in another projection technology, having recently retrofitted projection booths for sound-on-film or sound-on-disc projection. After runs in New York and Los Angeles, 35 mm prints of The Big Trail played smaller markets, but Grandeur prints returned to Warner Bros., unused, tattered, and essentially forgotten. The next greatest widescreen thing didn’t happen…at least, not yet.

5. Frank Illo’s Sound Effects Machine. (Rube Goldberg sound producing device)

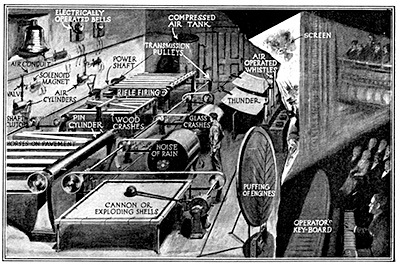

Illustration: Frank Illo Sound Effects Machine. Popular Science magazine, September 1919

To send sound coursing through a movie, one Dallas Texas inventor reasoned in 1918, one only had to install a Kasbah of noise-producing machines behind the screen to puff, bang, wheeze, rap, and tintinnabulate when cued by an operator sitting at a keyboard before the screen. Frank Illo patented the gizmo in 1918. The idea had a certain appeal. It imported to silent movie sound production the assembly line approach to creation that Henry Ford and others had implemented since 1914. Popular Science featured Illo’s concept in a multi-page spread in 1919, but no theater operator seems ever to have installed Illo’s next greatest thing. Within a decade, synchronous sound systems supplanted sound making gizmos and theater musicians. Frank who?

6. Hale’s Tours. (Simulator theaters)

Left: Hale’s Tours, c. 1907. Right: Frame from a Hale’s Tours Movie: “A Trip Down Market Street Before the Fire” (1906)

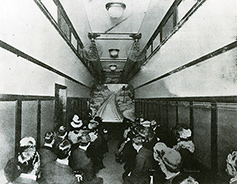

4D theaters with seats that twitch and vibrate aren’t revolutionary concepts. They return us back to 1905, when George C. Hale, a Kansas City fire chief, installed a simulated railroad car in a Kansas City amusement park. Within two years, “Hale’s Tours” shook and shimmied in 500 cities across America and others abroad. Up to seventy two virtual “passengers” would gather for a “journey.” Ahead on a screen played a one-reel movie shot from the front of a moving streetcar or railroad train. Outside gears shook the “carriage,” simulating travel. Whistles “blew,” wheels “turned,” and fans whipped up breezes. Painted landscapes unscrolled behind the side windows. A “conductor” collected tickets, announced stops, and oversaw the operation. Already in 1905, you climbed aboard the movie train and, until people tired of the gimmick by 1911, you headed to Shining Time station.

The next greatest thing of the movies regresses into the future where perpetually it becomes something else. But imagination is always here and present. Imagination is the key to making movies.

Robert Gerst is the author of Make Film History: Rewrite, Reshoot, and Recut the World’s Greatest Films, from Michael Wiese Books.