There is a long history of literary writers crossing over into screenwriting, whether it be to adapt their own work, create something new, or adapt the work of others. Some of them have made this transition with great success, and have been able to translate their written voice into a visual medium. Many others, however, this transition has not been so fruitful, or has, at the very least, been a mixed bag. On the other hand, there are countless examples of literary writing being adapted by other screenwriters, which comes with its own challenges, failures, and success stories. Looking at these various situations is important to come to a better understanding of what works, and what does not, so that film, as a medium and industry, can utilize the brilliant stories and the people who created them.

Letting Go

Inherently, filmmaking is a collaborative effort between people filling a wide-variety of roles and responsibilities. While the entire arc of the story the film is telling may be found on the pages of its screenplay, the story itself is not complete in this form. In order for these stories to truly accomplish their goals, the written form needs to be brought into an animate existence through the work of directors, producers, the cast, cinematographers, and other crew.

This aspect of filmmaking is key to the disconnect between cinematic and literary writing. The archetypical author is a booze-soaked person of solitude, and their art is used to either express or combat deep loneliness and isolation. While this image is absolutely perpetrated and exaggerated by cultural fetishization of authors like Faulkner and Hemingway, there is some truth there.

Corey Stoll as Ernest Hemingway in Midnight in Paris. Image courtesy of PopMatters

Writing is largely a solitary art form, at least in its initial stages. At the workshopping or editing stages, collaboration becomes a more regular part of the process, but it still pales in comparison to filmmaking in sheer number of people working on one project. Bringing additional people into this process, which has been so largely individualistic for the writer, takes away a large amount of creative control that they normally have. Even if they are free to complete their screenplay within the comforts of their normal writing process, once it goes into actual production, it is in the hands of other people.

To Adapt or Not?

When literary writers do move into screenwriting, there is also questions over whether or not they should adapt their own literary work. On one hand, nobody is closer and more familiar with a piece of fiction than the person who created it. This can make it possible for a smooth transition into film, since the person writing it knows how the story moves and breathes, and how the characters function in a more fully developed way than someone who simply reads the book might. However, this can also hinder the screenwriting process. When adapting a piece of literature into film, changes and cuts are absolutely necessary. It can be incredibly difficult for an author to make these kind of changes, though. It requires them to let go of things they hold dear in their original work. When someone spends as much time as a writer does on something, the last thing they might want to do is eliminate something for the sake of telling their story in under three hours of screen time.

Truman Capote, while best known for his literary works, was also highly skilled as a screenwriter, playwright, and actor. He received a Golden Globe nomination for his writing, was well-received as a playwright, and multiple films about his life would eventually be produced, most notably Capote, for which Phillip Seymour Hoffman won an Academy Award portraying Capote. His nonfiction novel, In Cold Blood provided the world with a close, realistic perspective on real world crime that was devoid of many inaccuracies that are so heavily ingrained into the public conscious through TV and film portrayals. The writing in this book is so undeniably influential that he is not only considered to have influenced literature, but journalism as well.

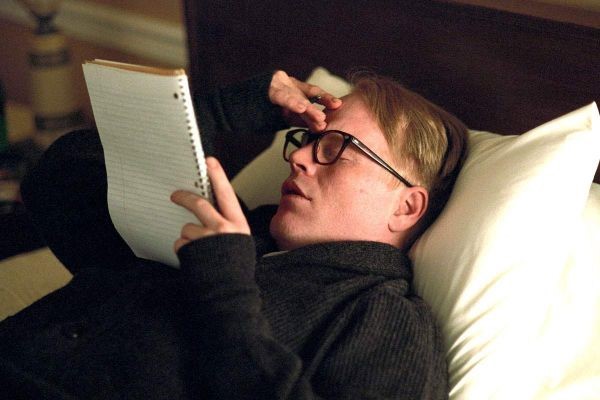

Phillip Seymour Hoffman as Truman Capote. Image courtesy of The Movie Network

However, despite his numerous TV and film writing credits, his most renowned books, Breakfast at Tiffany’s and In Cold Blood were adapted by other writers. Both of these films were nominated for Academy Awards in Best Adapted Screenplay. In the case of Breakfast at Tiffany’s, we have a substantial case for the validity of authors passing their work off to other screenwriters. The film veered away from the novel in favor of a more whimsical and lighthearted tone, specifically in its conclusion, which resonated with audiences at the time of its release in a way that a more faithful rendition would not have. In order to make the fairy-tale ending of the film possible, it also changed the sexual orientation of the narrator to heterosexual, which, again, gave the film larger mass appeal, despite betraying a theme that was important to Capote in writing the novel.

On the other side of the spectrum, however, we have a films like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, which succeeds as a film because of changes made from the source material that actually are more likely to alienate or confuse an audience upon first viewing.

In this instance, we see a filmmaker taking literary work and sculpting it to tell a story that thrives in a visual medium in a way that the book would not. Kubrick’s cinematography overall visual work on The Shining is absolutely singular, and only works because of the amount of time that the film takes focusing on it. The long tracking shots and time between cuts would not work if the film also spent the time that would be necessary to fully portray themes like alcoholism and a dissolving family structure, in the same way the novel does.

There are instances, however, when an author has adapted their own work and been successful. John Irving won an Academy Award in 2000 for the adaptation of his book The Cider House Rules, as did William Peter Blatty for The Exorcist. While both of these films received acclaim, neither were first screenwriting efforts. Both of these writers had done previous film work, with Irving having previously adapted his own work in The World According to Garp (with the help of Academy Award winner Steve Tesich), and The Hotel New Hampshire. Blatty had worked in film for over a decade before The Exorcist, but also got his start collaborating on the second film in the Pink Panther series, A Shot in the Dark with renowned director, Blake Edwards, (who incidentally directed Breakfast at Tiffany’s).

Stephen Chbosky went even a step further and directed his adaptation of his book The Perks of Being a Wallflower. This was Chbosky’s first directorial effort since he began his career by directing the independent film The Four Corners of Nowhere in 1995. The success of this film seems surprising, then, considering Chbosky’s lack of professional experience. However, Chbosky is not a typical literary writer, and actually comes from a film background first, having received a degree from USC’s acclaimed screenwriting program in 1992, before concentrating on literary endeavors.

Stephen Chbosky on the set of The Perks of Being a Wallflower. Photo The Movie Network

Conclusion

While there are certainly exceptions in authors such as Nick Hornby and Dave Eggers, the transition from literary to screenwriting is generally not one that is made without either collaboration or a previous background in film. While this is not necessarily damning of all screenwriting attempts from authors, it does show that these mediums are distinct enough to create massive challenges. However, these challenges should not inherently dissuade literary writers from attempting to crossover. What it does mean, however, is that they should approach it with a more open mind, especially toward collaboration, than they might be used to working with. There are many fresh and creative voices within the literary world that would be a beautiful addition to film, but these voices need to be guided to a place where their work translates effectively into film. Regardless of how many can make this jump, each time there is success, either from an adaptation of a literary work, or a literary writer moving to screenwriting, the filmmaking world should celebrate.